German and Dutch are both Germanic languages, and so similar that German speakers often learn Dutch relatively quickly. That’s why we organise the Fast tracks for German speakers, special courses in which you’ll go through a course program twice as fast as in our regular courses. We offer these courses for the levels A1.1 & A1.2, A2.1 & A2.2, B1.1 & B1.2 and B1.3 & B1.4.

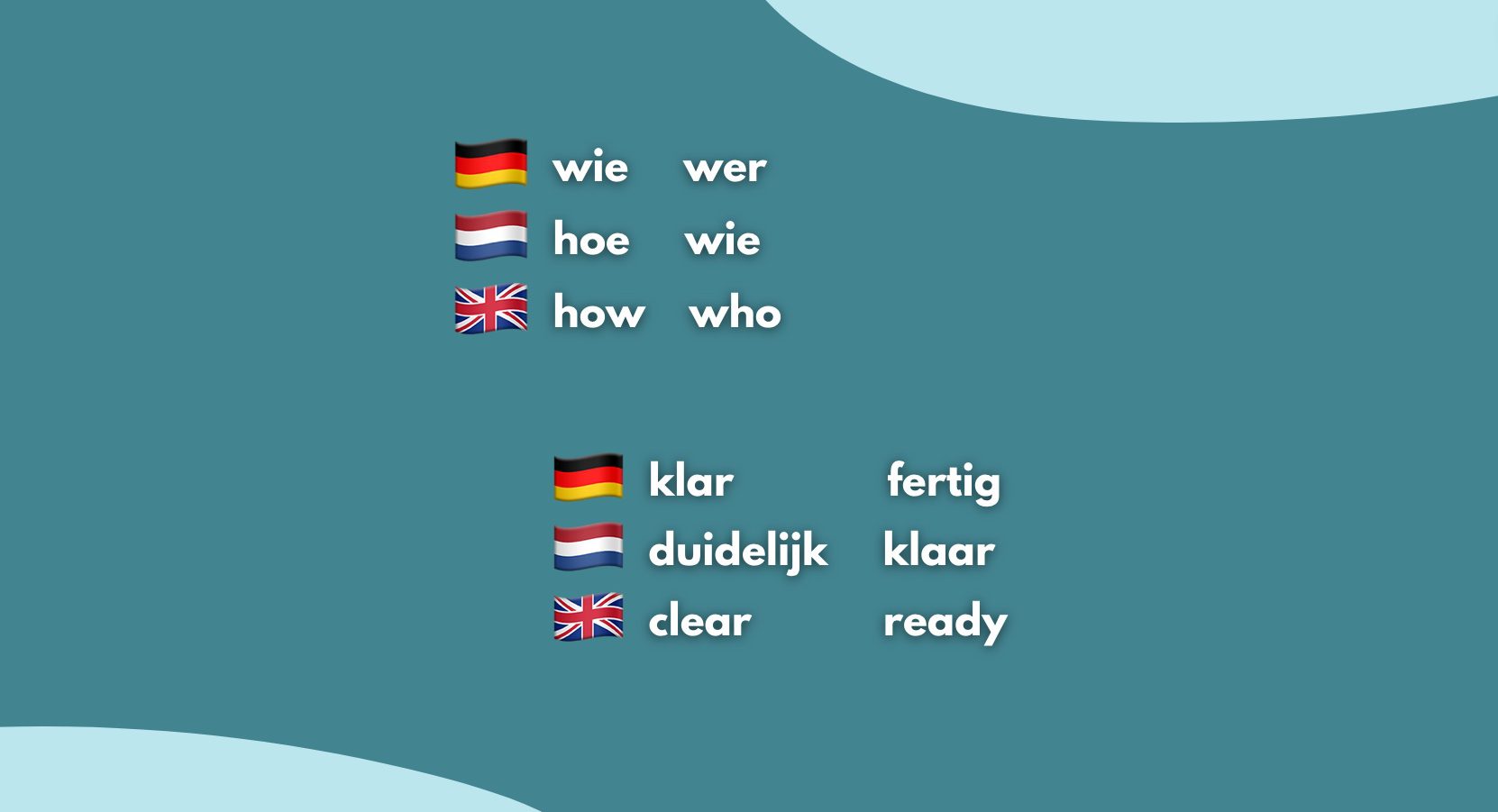

The fact that Dutch and German are so similar also hides some traps, or so-called false friends: think of wie for example, which means ‘how’ in German, but ‘who’ in Dutch. Some of these falsche Freunde were already mentioned in our blog about linguistic false friends in general. For now we’ll take a closer look at the German ones, and at some sentence constructions that could easily mislead you.

If you want to get klar (‘clear’ in German) what you’re talking about – and not klaar, because that means ‘ready’ in Dutch – it’s quite slim (‘smart’ in Dutch) to pay close attention to these kinds of subtle differences. Not to be confused with schlimm, which means ‘bad’ in German. (The meaning of the original Proto-Germanic root slimbaz was ‘oblique’ or ‘crooked’, and while this lead to a negative connotation in Germany, it wasn’t that schlimm in the Netherlands.)

The word als is also a tricky one. You can use this word for ‘when’ if you’re telling about something that happened in the passed in German, but not in Dutch: als ich zur Großmutter ging is fine, but als ik naar grootmoeder ging is not. When referring to something in the past in Dutch, you need to use toen. The word als is used in Dutch though, but rather when talking about conditions – like with ‘if’ in English (Als je het woord ‘als’ gebruikt…), which would be wenn in German. Als can also mean ‘as’ in Dutch (Nederlands is net zo makkelijk als Duits), just like wie in German. Are you still with us?

If you want to ask the teacher to write something on the blackboard, it is better not to say tafel, because that does not mean ‘blackboard’, as in German, but ‘table’. Both come from the Latin word tabula, meaning a wax-covered tablet used for notes – you might also be familiar with the term tabula rasa, a clean slate. At the same time it also evolved in words like table, tavolo or tafel.

The Dutch word tuin looks familiar to the German Zaun, but they mean different things: garden and fence. That does make sense though: both words go back to the same Germanic root tūnan, meaning fence. In Dutch, the meaning shifted to ‘enclosed space’. The same happened in English, although there it became town – another enclosed space, as cities used to be fenced strongholds, back in the days.

Do you like to swim in the sea? For Germans it might sound logical to say Ik mag in het meer zwemmen, but in Dutch that would mean that you’re ‘allowed’ to swim in a ‘lake’. Two things to point out here: first of all, Dutch people would say zee instead of Meer, and meer instead of See – it’s just the other way around. The Proto-Germanic root mari could refer to both, but at some point it became ‘sea’ in Dutch, and also in the Low German dialects that are strongly related to Dutch and spoken in the north of Germany. There you could also find the Zwischenahner Meer – a lake.

So in Dutch you would say you like to swim in a zee, but besides that, it would be better to say Ik houd van in de zee zwemmen instead of Ik mag. In Dutch you rather use mag to ask permission: mag ik iets vragen? In German the word dürfen would make more sense, which is very similar to the Dutch durven. But that means ‘to dare’ – Ik durf geen toestemming te vragen.

If you come across a barking dog on the beach, you can’t use the word bellen to describe the action, as you would say in German, but blaffen. A bellende hond would be very interesting, since this word means ‘to call’, but then the dog first needs to know how a phone works. And that would be a bit weird, or seltsam as you would say in German – not to be confused with the Dutch zeldzaam, which means ‘rare’. Although that would be a fair statement just as well.

There are also some traps in the field of grammar. Take, for example, the sentence Ich weiß nicht, ob ich zur Party gehen will. In Dutch you would rather use ‘gehen’ and ‘will’ the other way around: Ik weet niet of ik naar het feestje wil gaan – in principle, we put modal verbs in a dependent clause before the infinitive, not after it. In principle, because it does occur in parts of the northeast of the Netherlands, and in music and poetry: think, for example, of the song Harder dan ik hebben kan by Bløf. But in colloquial terms, Ik weet niet of ik naar het feestje gaan wil sounds a bit old-fashioned to the most Dutch people – or poetic, depending on how you see it.

Fortunately, many things are also a lot simpler in Dutch. Verb conjugations are always the same in the plural: where in German you say wir sprechen, but ihr sprecht, in Dutch you would say wij spreken and jullie spreken. And more importantly: the articles do not change when the word is placed in a different case. In German you have to change der to dem, den or des, but in Dutch de stays just de and het just stays het. The Dutch language only has two articles at all: de and het, where het is the equivalent of das and de of die and der together.

Nouns are not inflected in Dutch, but adjectives are: you say het grote huis, but also een groot huis. Adjectives always end in an -e, unless it’s a word that has the article het (such as het huis) and it’s used in the indefinite form (such as with een, rather than the definite article de). Long story short: if it’s a het-word without a het, the adjective is without the e.

It’s klar that Dutch presents some challenges for German speakers, so there’s a good Grund to register for one of the Fast tracks for German speakers. (Grund means ‘reason’ in German, not to be confused with the Dutch word grond, which is Boden in German. Tschüss!)

Blog by Dutch teacher Yoran.